February 25, 2025

by Jacob Pattison and Stephen T. Messenger

Mary’s team of four in budgeting was all over the place. She knew it wasn’t unusual, but every person was at a different level of competence and development. When she sat them down in the mornings for a quick huddle to provide daily direction, some of them got it and some did not.

Just yesterday, after tasking them with a fairly easy assignment, one of them immediately got to work and completed it by noon, while another stared at the task until the end of the day before coming back to ask for additional assistance. Why couldn’t they all just get it done and move on to the next thing?

She took a breath to clear her mind. In the quiet moment, she remembered a presentation given by Bryan a few months back on leading people based on their skillsets and not the boss’ leadership style. She grabbed a notebook and slipped out of the office, heading to Bryan’s wing. Maybe he could give her a quick refresher.

When she arrived, Bryan was surrounded by his sea of whiteboards in the office with drawings everywhere of different solutions to problems. She ignored the images and explained her issue to Bryan. He gladly found some empty board space and launched into another drawing.

The Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership Model

Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard developed the Situational Leadership Model in their book Management of Organizational Behavior. It’s stating exactly what you’ve discovered with your team—there’s no single best style to lead people. The best bosses can understand how the complexity of a certain task relates to an individual person based on their skills and willingness to complete it. The one in charge must adapt their leadership style based on the person, not lead everyone the same.

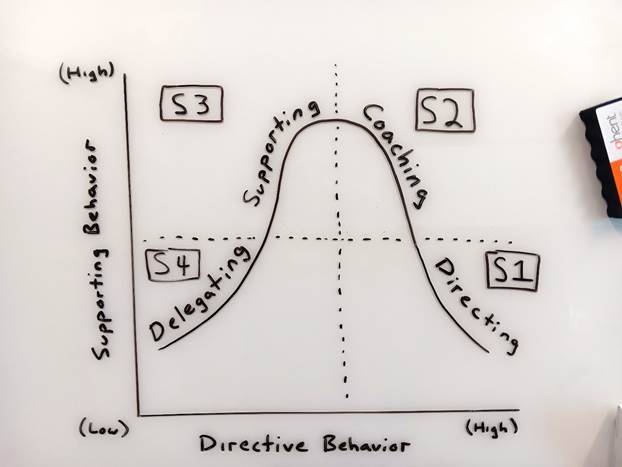

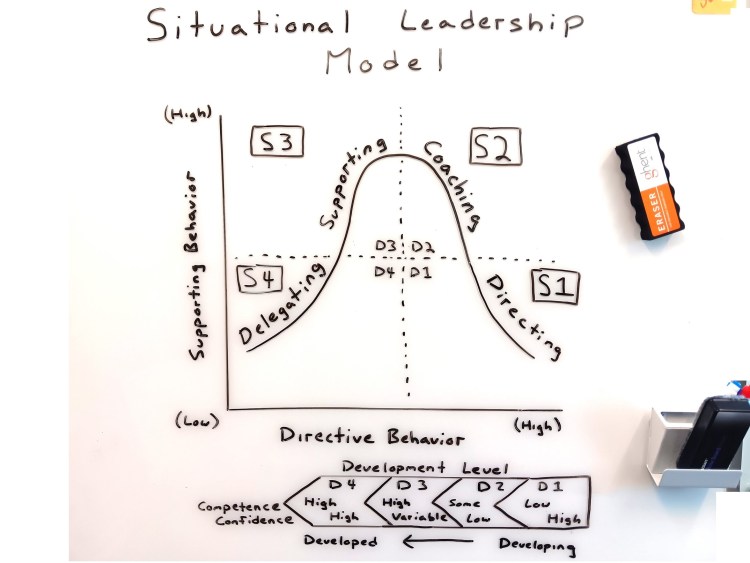

Hersey and Blanchard talked about the four main leadership styles of directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating. If I draw a graph, the x-axis is the level of directive behavior, and the y-axis is the level of supporting behavior. Directive behavior is the focus on getting things done and completing tasks. It’s making sure we are successful as an organization. Supporting behavior is the focus on people. It’s about building relationships with others, making sure they’re taken care of, thinking about morale, and looking out for them as valued members of our team.

Directing. On the chart, the directing style is in the bottom right corner. This is when leaders provide detailed instructions on how to complete the task then supervise that person closely. It has a high directive component because we’re telling them what to do and a low supportive component because we’re not as concerned about the person, but about being successful today. I think of this as the Army’s Basic Combat Training or boot camp.

When they arrive, soldiers are new to everything, and drill sergeants tell them exactly what to do and when to do it without any ambiguity. The instructors are in their faces all day long with detailed instructions and little care for feelings. New Soldiers are expected to complete their tasks as directed with constant oversight from drill sergeants. This dynamic generally persists as new soldiers are integrated into their first units. Their leaders ensure that new unit members can accomplish basic tasks as directed before they can begin a more structured development process.

Coaching. The top right of the chart is the coaching style where there is still a directive component but not as much. Here leaders ramp up support to the person and start involving them in decision-making. Employees still require a significant amount of being told what to do, but two-way communication increases. This part is designed to help others gain confidence in their skills by talking through problems with a coach by their side. In the Army, soldiers attend the Basic Leader Course before supervising soldiers to learn how to lead others. Unlike basic training, the instructors at the course do a lot less directing (yelling) and more coaching to teach them how to lead others effectively.

This is the first level of Army leadership training that introduces experiential learning among students. The instructors, also called small group leaders, are trained to facilitate conversations in the classroom that draw out experience. Instructors use this information to identify gaps in student knowledge so they can better understand how to support student development throughout the course. Graduates of the course have a solid leadership foundation but will still require support and direction from their leaders.

Supporting. The top left of the chart is the supporting style where the boss provides less instructions on how to complete a task but talks more about what needs to be done. It is a collaborative style where leaders focus on listening, encouraging, praising, and demonstrating trust. Here leaders believe that the employee has the skills and knowledge to complete the task, and leaders support them in any way possible to get the ball across the line. The Army conducts an Advanced and Senior Leaders Course to develop squad leaders and platoon sergeants. Here, there is much less directive action and high emphasis on the student preparing to lead others. They support them in their journey.

Squad leaders and platoon sergeants are generally given more freedom of action to accomplish their assigned tasks. They are told what needs to be done and are free to determine the most effective or efficient way to make it happen. They can manage their people and resources with much less oversight than more junior leaders. These leaders have earned the trust that affords them more flexibility in how to complete tasks. Their leadership is still involved throughout the process, and they provide feedback and guidance as required.

Delegating. The final style of delegating is in the bottom left. Here, the leader is mostly hands off. The employee is self-sufficient and only needs a task and resources and will get it done. The boss tells them what task to do and doesn’t say much else. They back off and watch the employee crush the assignment with little to no oversight. They don’t completely abandon their followers but instead let them run! The Army’s senior school for non-commissioned officers is the Sergeants Major Academy. These senior leaders with decades of experience are responsible for their own learning. They receive an assignment, and they are trusted to read the material and learn themselves, unlike basic training.

Their classroom time is most productive when open dialogue occurs between students with vastly different operational backgrounds and perspectives. The sergeants major obtain value of drawing on the experiences of their teammates. When in the unit, the sergeant major receives guidance and intent from the commander, and makes things happen in their own way using their best judgment, competence, experience, creativity, and leadership. The sergeant major is given a task and trusted to deliver exemplary results without guidance.

Developmental Levels

Ken Blanchard goes on to explain that every employee is at a different developmental level or “D” category. This is the amount of skill they have to complete a task and the level of desire to get it done. Basically, it’s their competence and commitment levels that form an increasing scale from developing to developed followers.

D1 on the right side of the scale is low competence and high commitment or confidence. These are motivated people who want to succeed but they don’t know what they’re doing. Like basic training recruits, new employees, recently promoted leaders, or our child working on a new task, they are learning the job. They require a directive style of leadership being told what to do. Leaders of D1 employees should provide detailed instructions for tasks, and thorough oversight of employee performance.

D2 are those with some competence and low confidence. It’s not that they don’t want to succeed, it’s that they’ve increased in knowledge of the job but have become overwhelmed by everything they still don’t know. These are the Basic Leader Course students, employees expanding roles, or our kid moving from shooting hoops to basketball strategy. Leaders of D2 employees will generally need to adopt a coaching style where the employee and boss are partnered. Coaching can boost confidence and develop employee competence.

D3 are employees with high competence and variable commitment or confidence. These are people with lots of experience but like us all have the highs and lows of motivation. This may be due to personal situations, culture changes, family issues, or levels of recognition. They need support, guidance, and encouragement like the Army NCOs gaining increasing responsibility at leaders courses, seasoned managers, solid citizens who have been around a while, and teenagers. They require a supporting style taking ownership of their career. To maximize D3 performance, leaders must understand what motivates their employees. They should also provide support to encourage a higher degree of autonomy or independence.

Finally, D4 are employees who have high competence and high commitment and confidence. They are getting after it every day and don’t need to be told what to do. They are self-motivated and have the skills to succeed. They often go above and beyond. These are the senior Army leaders like sergeants major, exceptional employees, those bought into the mission, and hopefully our kids in college and beyond. They require a delegating style of leadership with minimal direction and all trust. Leaders of D4 employees can simply provide their intent and any relevant guidance, then focus their efforts elsewhere as the employee knocks it out of the park.

Matching Styles with Development Level

As you see, leaders have lots of styles to choose from and different employees are at different levels. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. It’s up to us to understand what level the employee is at and then match the leadership style to that person.

Mary was furiously taking notes, and she looked up at the whiteboard. “Yeah… I’ve been treating everyone the same. I probably need to think about each person and their needs instead of just giving them tasks and hoping they do them.”

Bryan smiled, “Well, I was always told hope is not a method, but if you can align developmental levels with leadership styles, I think things are going to change a lot for you.”

Jacob Pattison is a student at the U.S. Army Sergeants Major Academy. He is also pursuing a master’s degree in environmental management and policy. He has over 22 years of service in the Army, filling leadership positions from team leader to first sergeant. In his spare time, he enjoys hanging out with his family and being in the great outdoors.

Leaders read, think, discuss, and write about leadership. Your first step should be to sign up for The Maximum Standard’s weekly email where you’ll get a leadership vignette delivered for free every Tuesday morning! This could also be your year to get published in the Maximum Standard—we’re always looking for authors.