January 21, 2025

by Stephen T. Messenger

Jane Breeze was sitting at her desk with head in hands. It’s been a challenging three weeks since she implemented her new project: realigning roles and responsibilities within her team. With three of her people now working on tasks they had never done before, their productivity took a hit, and everyone noticed.

Four months ago, she pitched this to the senior leaders. They were admittedly risk averse, but after she convinced them of the long-term benefits they wholeheartedly agreed. Now productivity is down, the bosses are concerned, and her team is getting frustrated. This was unexpected because the plan was solid, and she took extra precautions to mitigate any issues.

She looked out the doorway and sighed. That’s when she saw Bryan at the end of the hall. He was on one of his daily strolls through the office, checking in with people to ask how they were doing. He was always talking to people and interested in their projects. “Why did he do that?” she wondered.

“Hey Bryan,” she called a little too loudly. She spoke a little softer: “You have a minute?”

Bryan listened with the calm demeanor he always carried. Jane noticed how nothing ever really seemed to shake him. By the time she unloaded her worries and problems on him about her failing change initiative, Bryan simply smiled and grabbed a whiteboard marker. “May I?” he asked.

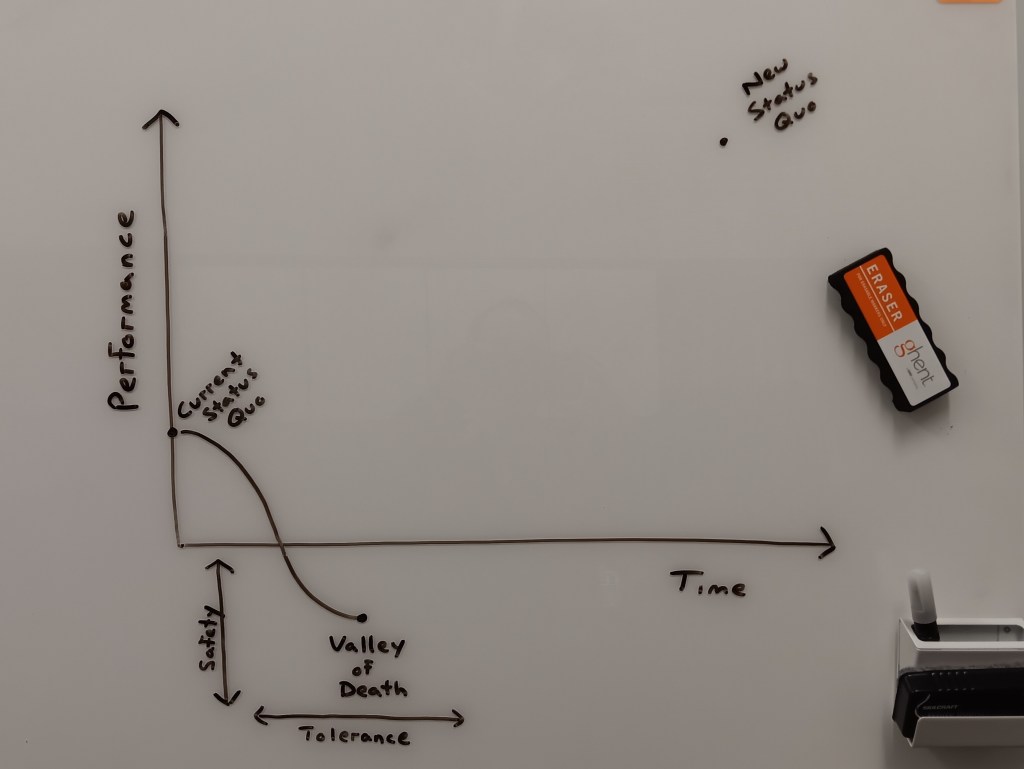

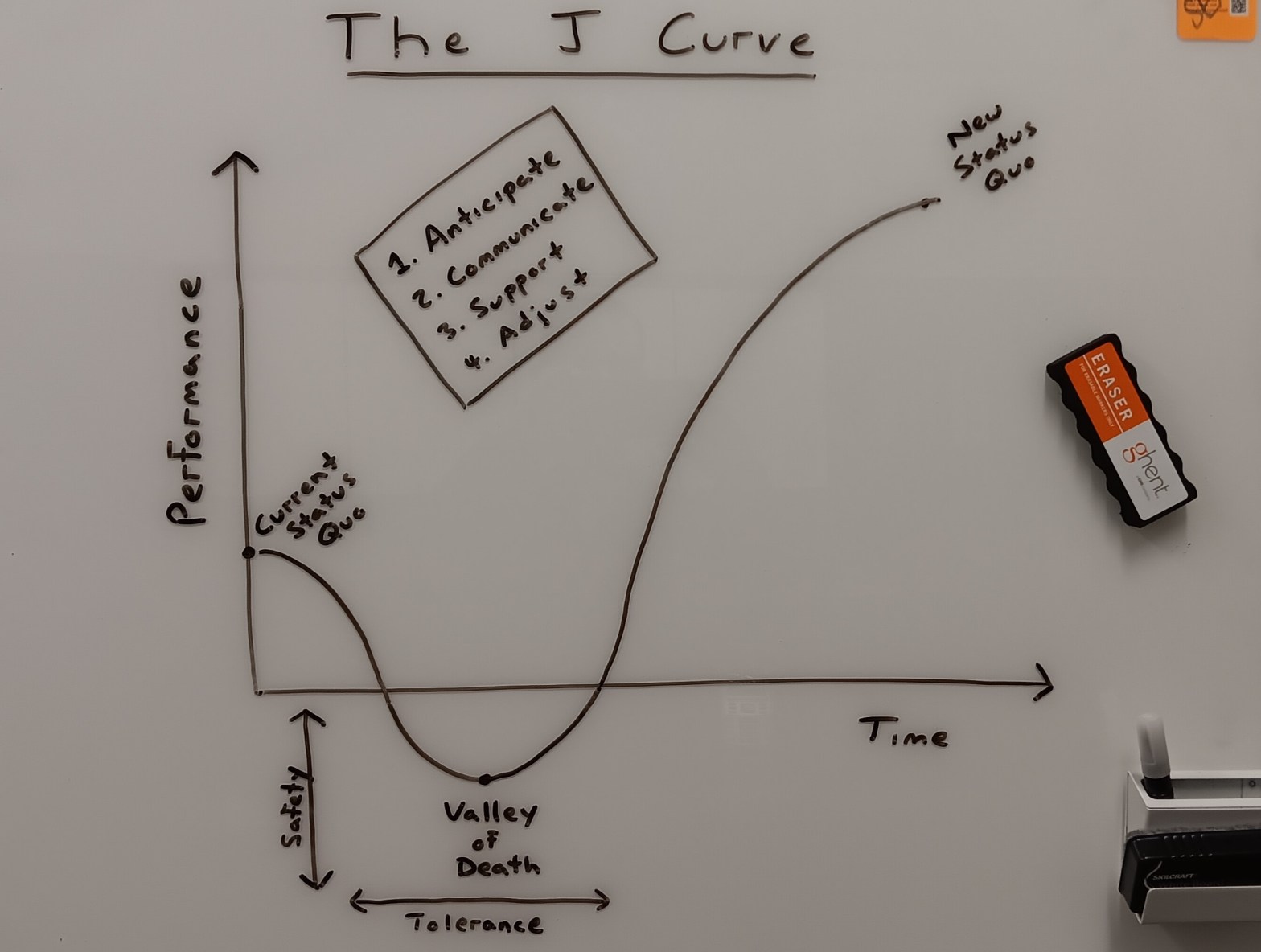

The J-Curve

Whenever we go through change, we experience a dip in performance. This is because we’re about to try new things that will invariably cause growing pains. It’s like when babies fall a lot when they begin learning how to walk. But the problem is that most people expect results now; they want to yell at the baby for trying. That’s why leading change is so difficult.

This chart I’ll draw represents our performance over time. Before any change occurs, we’re at the status quo. Without trying anything new, we’ll probably stay here forever. Our job as change agents is to improve the status quo and bring us to a point where we’re performing better.

When we first pitch our idea, we plant the seed of improvement to our team. They can all envision from our idea how it will make us better, smarter, faster, or stronger. They’re all on board! The real problem is that everyone in our organization thinks that there’s a straight line from our current state to our desired end state. But… that’s not going to happen.

Instead, performance during change is based off a J-Curve. This theory comes from Dr. Jerald Jellison in his book Managing the Dynamics of Change. He talks about the five stages of change and the performance, thoughts, and emotions that go along with it.

At the beginning of change, we’ll see a dip in performance because we’re all trying new things. For example, I once started a different workout routine where I ran on the treadmill at a 12% incline. During the first try, I was slower, felt terrible, and was way out of breath compared to my normal runs. The next day, I had trouble walking.

Here, I had fallen into this “period of disruption.” Initially, there’s an adverse impact on performance, and it all qualifies as risk to the organization. The depth of the dip is the amount of safety I and everyone around me are willing to accept. On the treadmill, if I want less safety I could lower the incline. This may not give as much benefit in the long run, but it will lessen the risk. Or, I could raise the incline to 15% and feel more pain with the confidence of larger gains at the end.

The length of the dip is how much we can tolerate before we quit. When we have these dips in performance, people are going to be upset, especially bosses. If they don’t see improvement, they may want to pull the plug. That’s how I felt running on an incline. After a few days, I wanted to unplug my treadmill and never use it again because of the initial pain.

The low point in this curve is the “Valley of Death.” This is where change initiatives go to die. Did you know the second Friday of every January is called “Quitter’s Day?” It is the point where people reevaluate their goals and decide whether going to the gym or eating healthy is worth it. They give up on their vision of the future. About 12 days into my incline running was the day I wanted to quit. But four strategies can get us through this valley.

1. Anticipate. Before change initiatives even start, the key is to anticipate the amount and length of disruption. In doing so, we can understand and articulate the risk to everyone around us, not just the boss, so we all know what to expect. Before I started running, I knew the incline was going to be uncomfortable, and I’d be sore the day after. I let everyone in the house know how great this was going to be for me, but that I may be moving slower than normal in the beginning.

2. Communicate. Once we know the risks, we have to communicate them far and wide to everyone affected. Our knowledge of the risks we’re about to undertake will reassure our stakeholders that we understand the full life cycle of this change and allow them ideas of how to participate. I told my wife that I was going to wake up earlier, be on the treadmill a little more, and probably be more tired in the evenings. Once I let her know, she even helped by suggesting a better diet to go with it.

3. Support. Next, we must have our support network in place. There are a number of technical, IT, systems, subject matter experts, educational, management, social, and emotional networks that need to be standing by to support our people in times of change. We have the resources, so we should use them. My change in exercise wasn’t just physical. I changed my diet, sleep habits, and time management. Most importantly, my wife and kids were cheering me on, which really helped.

4. Adjust. Finally, we must listen to feedback from the field and adjust as needed. Not all feedback will be constructive, but it should all be heard. It’s important to hear from the stakeholders, and it’s important they feel heard. After my first few hill climb workouts, my body was crying out for more water. I didn’t realize I needed so much hydration. Now I keep a water bottle on the treadmill and drink as I go.

Once we get past the risk phase and it’s uphill, we can’t stop there. It’s now time to celebrate the wins, communicate the change, and consolidate the gains we’ve made. We have to keep using the four strategies above even after we leave the period of disruption.

It’s never easy to get through change, but it helps when we realize what the change will look like and communicate it effectively to everyone. That’s how we can lead a team through change while understanding and dealing with the challenges that come with it.

Jane looked at the whiteboard with interest. “I feel like I did well in anticipating the risk, but I certainly didn’t communicate it effectively. Do you think that was the problem?”

Bryan gave a reassuring smile and pointed to the fourth strategy. “I think you’re adjusting well, and this is going to work out just fine. After all, I’m still running at incline. Keep at it!”

Leaders read, think, discuss, and write about leadership. Your first step should be to sign up for The Maximum Standard’s weekly email where you’ll get a leadership vignette delivered for free every Tuesday morning! This could also be your year to get published in the Maximum Standard—we’re always looking for authors. Lead well

I love this series and it’s only week two. I like that it’s giving us great tools to use with our teams. I’ve been advertising your blog in CES Intermediate.. thanks for all you do!!!

LikeLike

Todd, appreciate the feedback. I am incredibly excited to write these. As you can imagine, my whiteboards are filled with diagrams right now.

LikeLike